The Monty Hall paradox

Probability is one of the pillars of modern maths. We need to rely on it each time we do not have enough control over a system and so it is impossible to provide any deterministic description of its evolution. Although the unquestionable successes of this discipline in many fields of Science, our intuition is not always the key to solving the most subtle riddle. In fact, it is easy to come across tricky paradoxes like the famous Monty Hall paradox.

The Game

Suppose you are in a tv show and the presenter shows you $N$ closed doors. You are told that behind one of them there is a brand new car, while the others doors hide $N-1$ goats. You really need a car because you are a farmer, you have already many goats and you desperately need a way to reach the closest town to date your sweetheart.

At the first stage, you are asked to choose one of the $N$ doors. All the doors look the same, so you don't have any hint about where the car is.

Once your choice is made, the presenter will open $p$ of the remaining $N-1$ doors not hiding the car. The presenter knows where the car is, and he really wants you to win the car.

Finally, the presenter asks you: "Would you like to choose another among the remaining closed doors, or do you prefer to stick to your original choice?"

The case with 3 doors

Now that the rules of the game are clear, let's try to be more concrete and give an answer to the presenter, keeping in mind that we really desire to date your partner.

Suppose the doors are only 3. In this case, the probability we pick the winning door on the first shot is simply $\frac{1}{3}$. We know that the presenter will open a door hiding a goat, therefore at the end of the game we will have to choose between the two options:

- open the door we chose at the beginning;

- change the door, and open the door the presenter has not unlocked.

What the intuition of many may suggest is that the two options are equivalent: since we end up with two doors, and apparently we don't have any further help from the presenter, the probability to win the car is $\frac{1}{2}$, no matter what I will do.

This is wrong. If we decide to change the door, the probability to win is $\frac{2}{3}$, double of the probability of winning sticking to the first choice.

A Simple Proof

Let's go back to the generic formulation of the game, where we have $N$ doors and the presenter will open $p$ of them after the first choice, and let's focus on the probability of winning if we opt to change.

There are essentially two scenarios:

A. You choose the right door on the first shot

In this case, the probability to win after changing the door is simply $0$. Remember, there is only one car, and if you change your mind after pointing out the right door, you will find a goat.

B. You choose one of the wrong doors on the first shot

The probability of choosing the wrong door at the beginning is:

$$\frac{N-1}{N}$$

No matter which one of the $\frac{(N-2)!}{p!(N-2-p)!}$ set of $p$ doors the presenter will open, the probability to point out the right door among the remaining $N-p-1$ doors is:

$$\frac{1}{N-p-1} $$

Combining these two terms together, we get the probability of winning in this scenario:

$$\frac{N-1}{N-p-1}\cdot\frac{1}{N}$$

Before proceeding it is interesting to notice that for any choice of $N$ and $0 \leq p<N-1$,

$$\frac{N-1}{N-p-1}\geq1$$

where the equality holds when $p=0$, i.e. the presenter doesn't open any door. This means that it's always convenient to change the door, as we increase the probability of winning $\frac{1}{N}$ by a factor that is greater than 1.

Let's play

Although you are not invited to play this game, you can easily simulate the Monty Hall game and check the results just shown. The simplest way to do this is to prepare a python script that reproduces the steps of the game and finally plots a couple of graphs.

As usual, we need first to import the libraries we are going to use:

import numpy as np

import random

import matplotlib.pyplot as pltThen, let's build a class that reproduces the process:

class Monty:

def __init__(self,N,p):

self.doors = set(range(N))

self.p = p

self.car = {random.randint(0,N-1)}

self.guess = {random.randint(0,N-1)}

return

def open_doors(self):

doors_to_open = set(random.sample(self.doors-self.car.union(self.guess),self.p))

self.doors = self.doors - doors_to_open

return

def change_door(self):

new_options = list(self.doors-self.guess)

self.guess = {random.choice(new_options)}

return

def check(self):

if(self.guess==self.car):

return 1

return 0Each time an object Monty is initialized we need to pass as arguments the integer N for tweaking the number of the doors, and the integer p , which decides how many doors the presenter will open. The __init__ creates the attribute self.doors, a set of integers between 0 and N-1 which models the doors, and picks randomly the winning door, self.car and the first self.guess. Notice that I have used python sets to be able to perform the standard operations of union and subtraction of sets.

The method open_doors is designed to:

- draws a random sample of

pdoors from the set resulting from the operation of subtraction between the whole set of doors and the set containing the choice made and the winning door. As the name suggests, the variabledoors_to_openstores the doors that will be opened by the presenter. - reduce the set of still closed doors, by subtracting the set of the

pdoors to the original set of doors.

Finally, the method change_door makes another guess choosing from the set of the remaining doors, and check simply returns 1 if the chosen door matches the winning door, and 0 otherwise.

To run the entire process we can build this simple iteration.

win = [0]

loss = [0]

N_GAME = 500

for i in range(N_GAME):

game = Monthy(N=3,p=1)

game.open_doors()

game.change_door()

win.append(win[-1]+game.check())

loss.append(i+1-win[-1])

win = win[1:]

loss = loss[1:]win[i] is the number of successes after running the experiment i+1 times, while loss[i] is the number of losses until the same step.

Checking the results

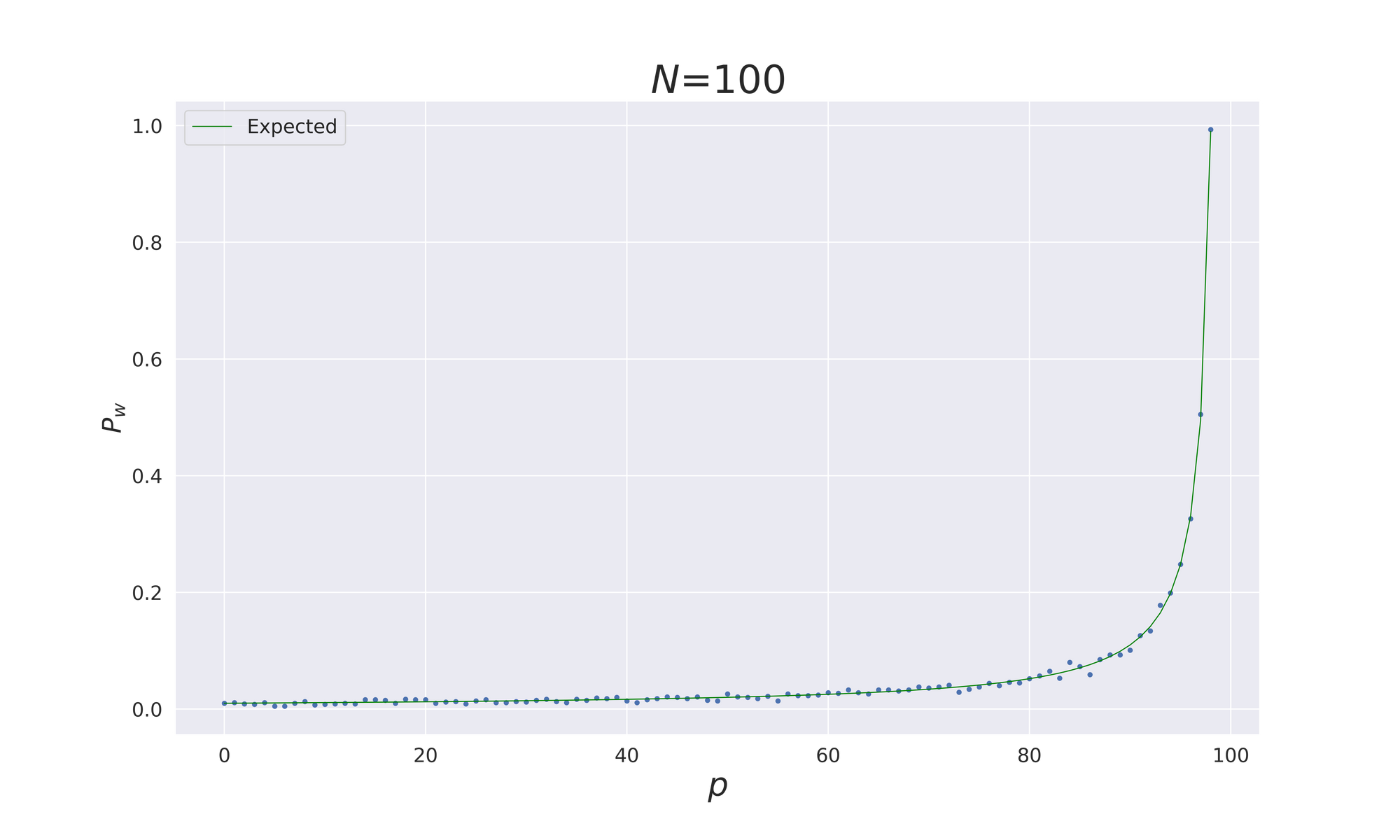

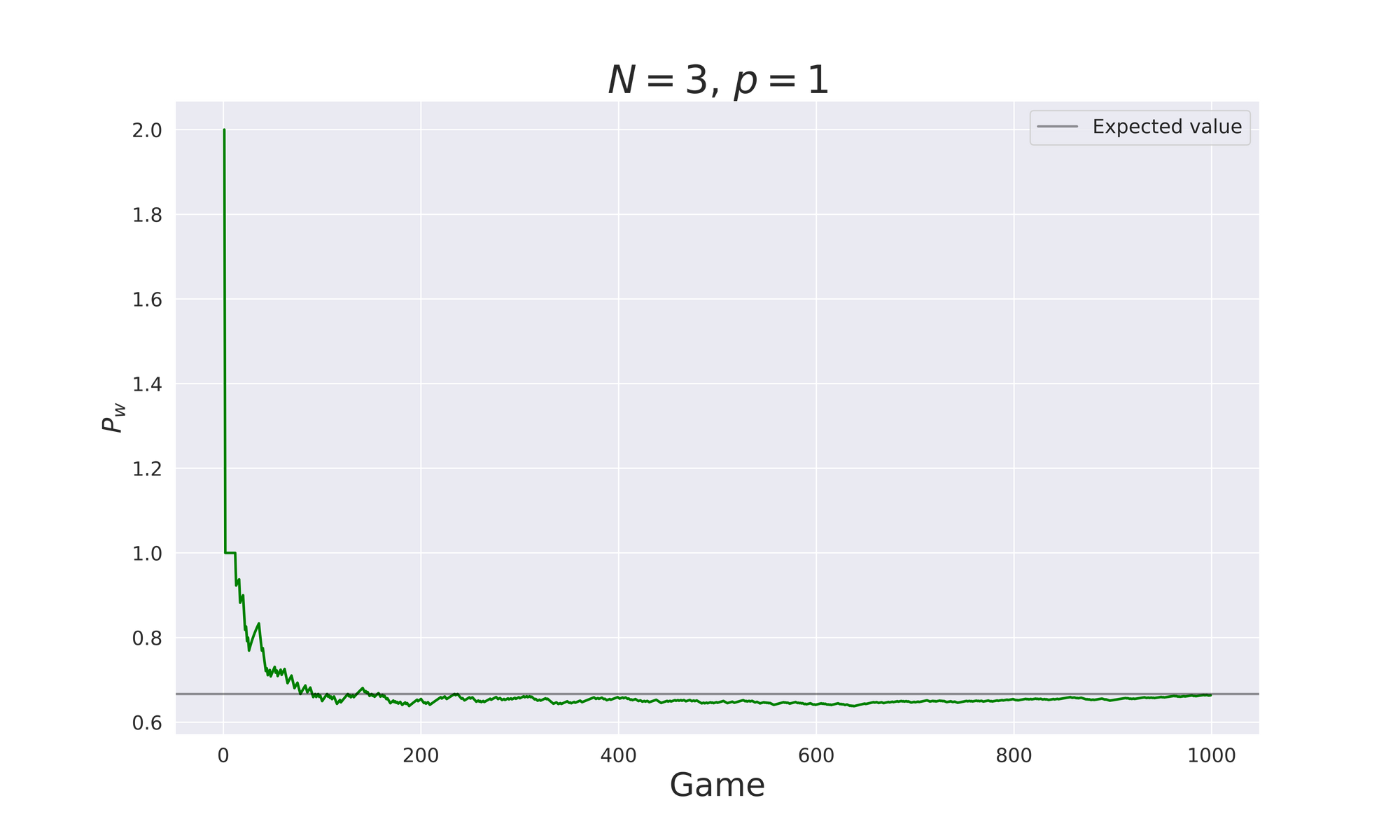

In the paragraph "A Simple Proof" we got the formula

$$P_{w}(N,p)=\frac{N-1}{N-p-1}\cdot\frac{1}{N}$$

for the probability of winning by changing the door. For $N=3$ and $p=1$ we have $P_{w}(3,1)=\frac{2}{3}$, and this is exactly what is shown in the plot below. We see that if we repeat the game many times, and for each simulation we take track of the winning, the ratio $\frac{win}{games}$ approaches the expected value.

The last takeaway message is that if we fix $p=N-1$, then

$$P_{w}(N)=\frac{N-1}{N}$$

which goes to 1 as $N \rightarrow \infty$. This is not a paradox result: if we imagine choosing the winning door among 1 million doors, and next 999 998 doors are opened, we do expect that the car is in the door that has been left closed. We would not be so optimistic to think to have picked the right door on the first shot!

In the plot below is shown $P_{w}(N=100,p)$ as function of $p$. The small dots are given by computing the ratio $\frac{win}{games}$ after iterating each process 1000 times, the green continuous line is the expected behaviour.